Philo Judaeus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(Replaced content with "{{Philo of Alexandria}} Cult Tilling of the Earth {{Allegory}} other books at <Br> http://thriceholy.net/furtherf.html http://www.earlychristianwritings.com...") |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Philo of Alexandria}} | |||

[[Cult]] | [[Cult]] | ||

Revision as of 08:18, 20 May 2022

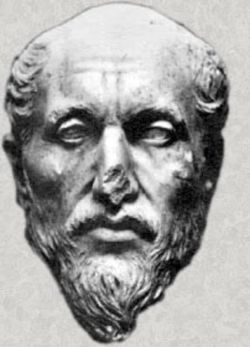

Philo Judaeus

Philo of Alexandria, also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt. Philo used philosophical allegory to attempt to fuse and harmonize Greek philosophy with Jewish philosophy.

Some scholars hold that his concept of the Logos as God's creative principle influenced early Christology. Other scholars, however, deny direct influence but say both Philo and Early Christianity borrow from a common source.

We find a brief reference to Philo by the 1st-century Jewish historian Josephus. In Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus tells of Philo's selection by the Alexandrian Jewish community as their principal representative before the Roman emperor Gaius Caligula.

He says that Philo agreed to represent the Alexandrian Jews in regard to civil disorder that had developed between the Jews and the Greeks in Alexandria, Egypt. Josephus also tells us that Philo was skilled in philosophy, and that he was brother to an official called Alexander the alabarch.

- "There was now a tumult arisen at Alexandria, between the Jewish inhabitants and the Greeks; and three ambassadors were chosen out of each party that were at variance, who came to Gaius. Now one of these ambassadors from the people of Alexandria was Apion, (29) who uttered many blasphemies against the Jews; and, among other things that he said, he charged them with neglecting the honors that belonged to Caesar; for that while all who were subject to the Roman empire built altars and temples to Gaius, and in other regards universally received him as they received the gods, these Jews alone thought it a dishonorable thing for them to erect statues in honor of him, as well as to swear by his name. Many of these severe things were said by Apion, by which he hoped to provoke Gaius to anger at the Jews, as he was likely to be. But Philo, the principal of the Jewish embassage, a man eminent on all accounts, brother to Alexander the Alabarch, (30) and one not unskillful in philosophy, was ready to betake himself to make his defense against those accusations; but Gaius prohibited him, and bid him begone; he was also in such a rage, that it openly appeared he was about to do them some very great mischief. So Philo being thus affronted, went out, and said to those Jews who were about him, that they should be of good courage, since Gaius's words indeed showed anger at them, but in reality had already set God against himself." Antiquities of the Jews, xviii.8, § 1, Whiston's translation

His ancestors and family had social ties and connections to the priesthood in Judea, the Hasmonean Dynasty, the Herodian Dynasty and the Julio-Claudian dynasty in Rome. Philo visited the Temple in Jerusalem at least once in his lifetime.

Philo would have been a contemporary to Jesus and his Apostles. Philo along with his brothers received a thorough education. They were educated in the Hellenistic culture of Alexandria and Roman culture, to a degree in Ancient Egyptian culture and particularly in the traditions of Judaism, in the study of Jewish traditional literature and in Greek philosophy.

APOLOGY FOR THE JEWS

From Eusebius, P.E. 8.5.11 ff.[1]

(5.11) And first of all I will adduce what Philo says respecting the journey of the Jews into Egypt, of which he has given an account, following that which is given by Moses in the first book of the Pentateuch, to which he has affixed the superscription, "hypothetically;" where, arguing in behalf of the Jews as if he were addressing himself to their accusers, he speaks in the following manner, affirming, --

(6.1) That their ancient ancestor, the original founder of their race, was a Chaldaean; and that this people emigrated from Egypt, after having in former times left its abode in Syria, being very numerous and consisting of countless myriads of people; and that when the land was no longer able to contain them, and moreover when a high spirit began to show itself in the dispositions of their young men, and when, besides this, God himself by visions and dreams began to show them that he willed that they should depart, and when, as the Deity brought it about, nothing was less an object of desire to them than their ancient native land; on that account this ancestor of theirs departed and journeyed into Egypt, whether in consequence of some express determination of God, or whether it was in consequence of some prophetic instinct of his own; so that from that time to the present the nation has had an existence and a durability, and has become so exceedingly populous, as it is at this moment. (6.2) And then, after a few more sentences, he says, --And they were led in this journey and emigration of theirs by a man who, if you will have it so, was in no respect superior to the generality of his fellow countrymen, so incessantly did they reproach him as a trickster and one who deceived them with words. An admirable amount and kind of trickery and deceit no doubt it was, by which he not only completely saved the whole people which was oppressed by want of water and hunger, and by ignorance of the way, and in a complete state of destitution of all things, and led them forward as if in all prosperity, and conducted them through all the nations lying around, and kept them without any quarrelling with one another, and in a state of complete subordination and obedience to himself. (6.3) And this too, not for a short time, but for a period of such length, that it is not likely that even a single family would continue in perfect unanimity and prosperity for such a time; for no thirst, no hunger, no decay of body, nor fear of the future, no ignorance of what was to befall them, ever excited that deceived people, who were being led, as some will have it, to their destruction, to rise against him who was deceiving them. Yet what would you have us say? (6.4) That he had such excessive art, or such great eloquence of speech, or such shrewdness, that he could triumph over so many difficulties of such a nature, which seemed likely to lead to the destruction of them all? Surely you must confess, either that the natures of the men under him were not utterly ignorant or obstinate, but were obedient and not inclined to neglect a prudent care of the future; or else that they were as wicked and perverse as possible, but that God softened their obstinacy, and was, as it were, a leader to them in respect both of the present and of the future. For that of these alternatives which appears to you to be the truest of the two, appears equally to contribute to the praise, and honour, and admiration of the whole nation. (6.5) These things, then, are what I have to say about this exodus. But when they came into this land, how they were settled here, and how they got possession of the country, they show in their sacred records. And I moreover do not think it necessary to describe it as by way of history, but rather to enter into some speculations concerning them as to what was their natural and likely course. (6.6) For which of these two alternatives will you embrace? That while they were still very numerous, although at last they were evilly afflicted, still, while they were powerful and had arms in their hands, they took the country by force, fighting with and defeating both the Syrians and Phoenicians who met them in that their land? Or shall we suppose that they were unwarlike, and destitute of manly courage, and altogether deficient in point of numbers, and destitute of any supplies for war; but that they met with respectful treatment from those nations, and obtained their land from them, who willingly surrendered it to them? and that then immediately, or at no distant period, they built a temple, and did everything else which has any bearing on religion and piety? (6.7) For these circumstances, as it seems, would prove them to have been a God-loving people, and beloved by God, and confessed to be such even by their enemies; for those people into whose territories they had suddenly come, as if to deprive them of them, were of necessity their enemies. (6.8) And if they met with respectful treatment and honour from them, how can we deny that they surpassed all other men in good fortune? And what shall we say after this in the second place, or in the third place? Shall we speak of their admirable code of laws, of their obedience, or of their devotion, and justice, and holiness, and piety? But in truth they looked upon that man, whoever he was, who gave them these laws, with such excessive admiration and veneration, that whatever he approved of they immediately thought best also. (6.9) Therefore, whether he spoke, being influenced by his own reason, or because he was inspired by the Deity, they referred every word of his to God. And though many years have passed, I cannot tell the exact number, but more than two thousand, still they have never altered one word of what was written by him, but would rather endure to die ten thousand times than to do any thing in opposition to his laws and to the customs which he established. (6.10) After Philo has said this, he proceeds to give an abridgment of the constitution established in the nation of the Jews by the laws of Moses, speaking thus:--

(7.1) Now, is there anything among that people resembling these circumstances, anything which appears to be of a mild and gentle character, and which admits of invocations of justice, and pleas, and delays, and of assessments of damages, and on the other hand of counter assessments? Not a word, but every thing is simple, plain, and straightforward. If you indulge in illicit connexions, if you commit adultery, if you do violence to a child (for do not speak of doing so to a boy, but even to a female child); and in like manner, if you prostitute yourself, if you suffer any thing disgraceful contrary to what becomes your age, or appear to do so, or are about to do so, death is the penalty for such wickedness. (7.2) Again, if you behave with insult towards a slave, or towards a free person, if you confine such an one in bonds, if you lead him away and sell him, if you steal any thing, whether common or sacred, if you commit acts of impiety, not only by your deeds but even by any chance word, I will not venture to say against God himself (may God be merciful to us, and of the same opinion about these matters), but against your father, or your mother, or your benefactor, death is equally the penalty. And that too, not a common, or ordinary, or natural death; but he who has merely uttered a single impious word must be stoned, as having committed no inferior impiety. (7.3) He also gives many other injunctions, such as these, that wives shall serve their husbands, not indeed in any particular so as to be insulted by them, but in the spirit of reasonable obedience in all things; that parents shall govern their children for their preservation and benefit; that every one shall be the lord of his own possessions, provided he has not dedicated them to God, nor spoken of God as their owner; but if he has vowed them only by a single word, then it is not lawful for him to lay hands upon or to touch them, but he must at once separate himself from them all. (7.4) May I never be guilty of plundering the things which belong to God, or of stealing what has been offered and dedicated to him by others. And even, as I have said before, if a single word to that effect has unintentionally fallen from a man, he must, instead of taking away from what is already dedicated, add some offering of his own; for if he has said the word, he, by so speaking, deprives himself of every thing. But if he repents, or wishes to recall and amend what he has said, he shall be deprived also of his very life. (7.5) And the same principle extends to other things, of which he is the owner. If a man by any words dedicates that which is requisite to support a wife, she shall be sacred and entitled to receive the support. If a father makes such a promise to his son, or a master to his servant, the rule is the same. And the way in which a man may be released from any promise or vow which he has made in such a manner can only be in the most perfect and complete way, when the high priest discharges him from it; for he is the person entitled to receive it in due subordination to God. And the next way is that which consists in propitiating the mercy of God in behalf of those who are the more immediate owners of the thing vowed, so that he may not accept of what is thus dedicated, since it is necessary to them. (7.6) There are, besides these rules, ten thousand other precepts, which refer to the unwritten customs and ordinances of the nation. Moreover, it is ordained in the laws themselves that no one shall do to his neighbour what he would be unwilling to have done to himself. That a man shall not take up what he has not put down, neither out of a garden, nor out of a wine-press, nor out of a threshing-floor; and that absolutely no one shall take anything, whether it be great or small, out of a heap. That no one shall refuse fire to one who begs it of him. That no one shall cut off a stream of water, but that everyone shall contribute food to beggars and cripples, and that such shall have favour with God. (7.7) That no one shall keep any one from performing funeral honours to the dead, but shall even throw upon them so much earth as if sufficient to protect them from impiety: that no one shall violate or move, in any manner or degree whatever, the graves, or tombs, or memorials of those who are dead. That no one shall add bonds, or any evil, or heap any additional suffering on him who is in trouble. That no one shall eradicate the generative powers of a man. That no one shall cause the offspring of women to be abortive by means of miscarriage, or by any other contrivance. That no one shall treat animals, in any respect, in a manner contrary to the injunctions imposed, whether by God or by a lawgiver. That no one shall cause his seed to disappear. That no one shall enslave his offspring. (7.8) That no one shall apply a false balance, or an inadequate measure, or bad money. That no one shall tell the secrets of his friends in a foreign land. Where, in God's name, are these yokes of oxen of ours gone? And look also at other commandments besides these. It is ordained, that no one shall fix the residence of the parents apart from that of the children, not even if they are prisoners of war; nor that of a wife from that of her husband, even though a man may be her master, having purchased her lawfully. (7.9) These commandments now are of a more solemn and important character, but there are others of apparently a trivial and ordinary kind. It is not lawful, says the lawgiver, to strip a nest wholly of its young; it is not lawful to reject the supplication of animals of any kind whatever, which flee to you for refuge, not even if any of them are very insignificant. You may say, perhaps, that these things are of no consequence whatever, but still, at least, the law which speaks of these particulars is of importance, and deserving of all imaginable care and attention; and the declarations are important, and so are the curses which threaten those who violate these laws with destruction; and God looks over all such matters, and is an avenger and punisher on every occasion and in every place. (7.10) And then after a few more sentences he adds, --And if it should happen that during a whole day, or I should rather say, not one day only but many, and those too not coming immediately one after another, but with intervals between them, even intervals of a week at a time, the custom, as is always natural, which is drawn from ordinary days prevails. Do you not wonder, that not a single one of all these commandments has been violated? (7.11) Is not this a mark of great temperance and self-restraint, derived to them from practice alone, so that they act towards one another with perfect equality, and are able to derive strength from those actions if it be necessary? Surely not so; but the lawgiver thought that it ought to be derived from some great and admirable circumstance, that they should not only be competent to do other things in the same manner, but should also be imbued with a thorough knowledge of their national laws and customs. (7.12) What then did he do on this sabbath day? he commanded all the people to assemble together in the same place, and sitting down with one another, to listen to the laws with order and reverence, in order that no one should be ignorant of anything that is contained in them; (7.13) and, in fact, they do constantly assemble together, and they do sit down one with another, the multitude in general in silence, except when it is customary to say any words of good omen, by way of assent to what is being read. And then some priest who is present, or some one of the elders, reads the sacred laws to them, and interprets each of them separately till eventide; and then when separate they depart, having gained some skill in the sacred laws, and having made great advancers towards piety. (7.14) Do not these objects appear to you to be of greater importance than any other pursuit can possibly be? Therefore they do not go to interpreters of laws to learn what they ought to do; and even without asking, they are in no ignorance respecting the laws, so as to be likely, through following their own inclinations, to do wrong; but if you violate or alter any one of the laws, or if you ask any one of them about their national laws or customs, they can all tell you at once, without any difficulty; and the husband appears to be a master, endowed with sufficient authority to explain these laws to his wife, a father to teach them to his children, and a master to his servants. (7.15) And again, it is easy to speak in the same manner with respect to the seventh year, though, perhaps, one is not to say exactly the same things, for they do not abstain from all work as they do on the sabbath days, only they leave their land fallow till the next year, in order that so it may become productive; for they think that thus it becomes much better after having had this rest, and then that it may be cultivated again, and not be dried up and exhausted by the uninterrupted continuance of cultivation; (7.16) and you may see that a similar practice conduces to strength of body, for not only do intervals of relaxation contribute to health, but you may see too that physicians also enjoin a degree of rest at times from work; for what is incessant, and uninterrupted, and always the same, is likely to be injurious, especially in the case of hard work, the cultivation of the land. (7.17) And a proof of this is, that if any one were to recommend the people to cultivate the land itself much more, and to add this seventh year also, and should promise them that the usual crops of fruit should reward their labours, they still would not adopt his advice, for they think that they are not alone entitled to rest from their labours, and yet even if they were to do so, it would be nothing strange; but they think that their land also deserves a certain degree of rest and exemption, in order again to receive a fresh beginning of care and cultivation; (7.18) since, in God's name, what could hinder them from letting it out during the year of jubilee thus proposed, and then receiving its annual produce once a year from those who rented and cultivated it? But as I said before, they will not admit of any such expedient in any manner or degree whatever, out of care, as it seems to me, for the welfare of the land; (7.19) and this is truly a very great proof of their humanity and moderation. For, since they themselves rest from their labours during that year, they think that it is not right either to collect the fruits or crops which are produced, nor to lay up any thing which has not accrued to them from their own labours; but, as if God provided for them while the land is thus enjoying rest and regulating itself according to its will, they think that any one who chooses or who is in want, any traveller or stranger, may gather the fruit that year with impunity. (7.20) However, this is enough to say to you on these matters; for, as to the fact of this law existing among them with regard to the seventh day and seventh year, you will not inquire of me, as you have perhaps heard it often from many persons, both physicians, and investigators of natural history, and philosophers, who discuss this law about the seventh year, as to the effect which it has on the nature of the universe, and especially on the nature of man. This is what he says about the seventh day ... I shall be contented with the testimony of Philo on the present occasion, which he has given about the matter which I am here explaining in many passages of his treatises. And now do you take that work which he has written in defence of the Jewish nation, and read the following sentences in it.

(11.1) But our lawgiver trained an innumerable body of his pupils to partake in those things, who are called Essenes, being, as I imagine, honoured with this appellation because of their exceeding holiness. And they dwell in many cities of Judaea, and in many villages, and in great and populous communities. (11.2) And this sect of them is not an hereditary of family connexion; for family ties are not spoken of with reference to acts voluntarily performed; but it is adopted because of their admiration for virtue and love of gentleness and humanity. (11.3) At all events, there are no children among the Essenes, no, nor any youths or persons only just entering upon manhood; since the dispositions of all such persons are unstable and liable to change, from the imperfections incident to their age, but they are all full-grown men, and even already declining towards old age, such as are no longer carried away by the impetuosity of their bodily passions, and are not under the influence of the appetites, but such as enjoy a genuine freedom, the only true and real liberty. (11.4) And a proof of this is to be found in their life of perfect freedom; no one among them ventures at all to acquire any property whatever of his own, neither house, nor slave, nor farm, nor flocks and herds, nor any thing of any sort which can be looked upon as the fountain or provision of riches; but they bring them together into the middle as a common stock, and enjoy one common general benefit from it all. (11.5) And they all dwell in the same place, making clubs, and societies, and combinations, and unions with one another, and doing every thing throughout their whole lives with reference to the general advantage; (11.6) but the different members of this body have different employments in which they occupy themselves, and labour without hesitation and without cessation, making no mention of either cold, or heat, or any changes of weather or temperature as an excuse for desisting from their tasks. But before the sun rises they betake themselves to their daily work, and they do not quit it till some time after it has set, when they return home rejoicing no less than those who have been exercising themselves in gymnastic contests; (11.7) for they imagine that whatever they devote themselves to as a practice is a sort of gymnastic exercise of more advantage to life, and more pleasant both to soul and body, and of more enduring benefit and equability, than mere athletic labours, inasmuch as such toil does not cease to be practised with delight when the age of vigour of body is passed; (11.8) for there are some of them who are devoted to the practice of agriculture, being skilful in such things as pertain to the sowing and cultivation of lands; others again are shepherds, or cowherds, and experienced in the management of every kind of animal; some are cunning in what relates to swarms of bees; (11.9) others again are artisans and handicraftsmen, in order to guard against suffering from the want of anything of which there is at times an actual need; and these men omit and delay nothing, which is requisite for the innocent supply of the necessaries of life. (11.10) Accordingly, each of these men, who differ so widely in their respective employments, when they have received their wages give them up to one person who is appointed as the universal steward and general manager; and he, when he has received the money, immediately goes and purchases what is necessary and furnishes them with food in abundance, and all other things of which the life of mankind stands in need. (11.11) And those who live together and eat at the same table are day after day contented with the same things, being lovers of frugality and moderation, and averse to all sumptuousness and extravagance as a disease of both mind and body. (11.12) And not only are their tables in common but also their dress; for in the winter there are thick cloaks found, and in the summer light cheap mantles, so that whoever wants one is at liberty without restraint to go and take whichever kind he chooses; since what belongs to one belongs to all, and on the other hand whatever belongs to the whole body belongs to each individual. (11.13) And again, if any one of them is sick he is cured from the common resources, being attended to by the general care and anxiety of the whole body. Accordingly the old men, even if they happen to be childless, as if they were not only the fathers of many children but were even also particularly happy in an affectionate offspring, are accustomed to end their lives in a most happy and prosperous and carefully attended old age, being looked upon by such a number of people as worthy of so much honour and provident regard that they think themselves bound to care for them even more from inclination than from any tie of natural affection. (11.14) Again, perceiving with more than ordinary acuteness and accuracy, what is alone or at least above all other things calculated to dissolve such associations, they repudiate marriage; and at the same time they practise continence in an eminent degree; for no one of the Essenes ever marries a wife, because woman is a selfish creature and one addicted to jealousy in an immoderate degree, and terribly calculated to agitate and overturn the natural inclinations of a man, and to mislead him by her continual tricks; (11.15) for as she is always studying deceitful speeches and all other kinds of hypocrisy, like an actress on the stage, when she is alluring the eyes and ears of her husband, she proceeds to cajole his predominant mind after the servants have been deceived. (11.16) And again, if there are children she becomes full of pride and all kinds of license in her speech, and all the obscure sayings which she previously meditated in irony in a disguised manner she now begins to utter with audacious confidence; and becoming utterly shameless she proceeds to acts of violence, and does numbers of actions of which every one is hostile to such associations; (11.17) for the man who is bound under the influence of the charms of a woman, or of children, by the necessary ties of nature, being overwhelmed by the impulses of affection, is no longer the same person towards others, but is entirely changed, having, without being aware of it, become a slave instead of a free man. (11.18) This now is the enviable system of life of these Essenes, so that not only private individuals but even mighty kings, admiring the men, venerate their sect, and increase their dignity and majesty in a still higher degree by their approbation and by the honours which they confer on them.

ON PROVIDENCE (Fragment I)

From Eusebius P. E. 7.21.336bÐ337a

But that you may not think that I am here arguing in a sophistical manner, I will produce a man who is a Hebrew as the interpreter for you of the meaning of the scripture; a man who inherited from his father a most accurate knowledge of his national customs and laws, and who had learnt the doctrines contained in them from learned teachers; for such a man was Philo. Listen then, to him, and hear how he interprets the words of God.

Why, then, does he use the expression, "In the image of God I made Man,"{1}{#ge 1:27.A.} as if he were speaking of that of some other God, and not of having made him in the likeness of himself? This expression is used with great beauty and wisdom. For it was impossible that anything mortal should be made in the likeness of the most high God the Father of the universe; but it could only be made in the likeness of the second God, who is the Word of the other; for it was fitting that the rational type in the soul of man should receive the impression of the Word of God, since the God below the Word is superior to all and every rational nature; and it is not lawful for any created thing to be made like the God who is above reason, and who is endowed with a most excellent and special form appropriated to himself alone.

This is what I wish to quote from the first book of the questions and answers of Philo.

And the Hebrew Philo, in his treatise on Providence, speaks in this way concerning matter.

But concerning the quantity of the essence, if indeed it really has any existence, we must also speak. God took care at the creation of the world that there should be an ample and most sufficient supply of matter, so exact that nothing might be wanting and nothing superfluous. For it would have been absurd in the case of particular artisans, for them, when they are occupied in making anything, and especially anything of much value, to calculate the exact quantity of materials which they require; but for that being who is the original inventor of numbers and measures, and the qualities which exist and are found in them, to omit to take care to have just what was proper. I will speak now with all freedom, and say that the world had need for its fabrication of some precise quantity of materials, neither more nor less; since otherwise it would not have been perfect, nor complete in all its parts, being thoroughly well made, nor would it have been made perfect of a perfect essence.

For it is an indispensable part of a workman who is thoroughly well skilled in his art, before he begins making any thing, to see that his materials are exactly sufficient; therefore a man, even if he were most eminently skilled in the knowledge of other things, still if he were not able altogether to avoid error, which is so natural to mortals, would be very likely to be deceived in respect of the quantity of materials which he required when he was about to proceed to the exercise of art; sometimes adding to it as too little, and sometimes taking away from it as too much. But that Being who is, as it were, a kind of fountain of all knowledge, was not likely to supply anything in deficient or in superfluous quantities, inasmuch as he employs measures elaborated in a most wonderful manner, so as to display perfect accuracy, and all of the most praiseworthy character. But he who is inclined to talk nonsense, at random, will easily do it, looking upon the different works of all artisans as causes, and as having been made in a more excellent manner, either by the addition or by the subtraction of some material or other. But it is the peculiar occupation of sophistry to quibble and cavil; while it is the task of wisdom to investigate accurately everything that exists in nature.

ON PROVIDENCE (Fragment II)

From Eusebius, P.E. 8.14.386Ð399

These things then are what may be said on the subject of the world having been created. And the same man also says a great number of very novel and bold things in his treatise on Providence, on the subject of the universe being governed by prudence; first of all putting forward the propositions of the atheists, and then proceeding to reply to each of them in regular order. And I will now proceed to extract some of the arguments which he adduces, even though they may appear somewhat prolix, because they are nevertheless necessary and important, abridging indeed the greater portion of them.

(1) Now he conducts his argument in this way; these are his words.

Do you say then that there is providence in such a vast confusion and disorder of affairs? For, in fact, which of the circumstances and occurrences of human life is regulated by any principle or order? which of them is not full of all kinds of irregularity and destruction? Are you the only person who is ignorant that blessings in complete abundance are heaped upon the most wicked and worthless of mankind? such, for instance, as wealth, a high reputation, honour in the eyes of the multitude, authority? moreover, health, a good condition of the outward senses, beauty, strength, and unimpeded enjoyment of all good things, by means of an abundance of supplies and resources and preparations of every kind, and in consequence of the peaceful good fortune and good condition of the body? But all the lovers and practisers of wisdom and prudence, and every kind of virtue, everyone of them I may almost say, are poor, unknown, inglorious, and in a mean condition.

(2) Having said thus much with respect to the outward circumstances of, and a vast number of other things affecting, these men, he then immediately proceeds to refute the objections of his adversaries by the following arguments.

God is not a tyrant who practises cruelty and violence and all the other acts of insolent authority like an inexorable master, but he is rather a sovereign invested with a humane and lawful authority, and as such he governs all the heaven and the whole world in accordance with justice. (3) And there is no form of address with which a king can more appropriately be saluted than the name of father; for what, in human relationships, parents are to their children, that also sovereigns are to their states, and God towards the world, having adapted these two most beautiful things by the unchangeable laws of nature, by an indissoluble union, namely the authority of the leader with the anxious care of a relation; (4) for as parents are not wholly indifferent to even ill-behaved children, but, having compassion on their unfortunate dispositions, they are careful and anxious for their welfare, looking upon it as an act of relentless and irreconcileable enemies to insult and increase their misfortunes, but as the part of friends and relations to lighten their disasters: (5) and indeed in the excess of their liberality they even give more to such children than to those who have always been well conducted, knowing well that to these last their own moderation is at all times an abundant resource and means of riches, but that the others have no other hope except in their parents, and that if they are disappointed in that they will be destitute of even the necessaries of life.

(6) So in the same manner, God, how is the father of all rational understanding, takes care of all those beings who are endowed with reason, and exercises a providential power for the protection even of those who are living in a blameable manner, giving them at the same time opportunity of correcting their errors, and nevertheless not violating the dictates of his own merciful nature, of which virtue and humanity are the regular attendants, being willing to have their dwelling in the God-created world; (7) this one argument now, do thou, O my soul, take to thyself, and store up within thyself as a sacred deposit, and this other also as consistent with and in perfect harmony with it. Do not ever be so deceived and wander from the truth to such a degree as to think any wicked man happy, even though he may be richer than Croesus, and more sharp-sighted than Lyceus, and more powerful than Milo of Crotena, and more beautiful than Ganymede,

"Whom the immortal gods, for beauty's sake,

Did raise up from the vile earth to heaven,

To be the cup-bearer of mighty Jove."{1}{homer's Iliad 20.234.}

(8) Accordingly, such a man, having shown his own daemon, I mean to say his own mind, to be the slave of ten thousand thousand different masters, such as love, appetite, pleasure, fear, pain, folly, intemperance, cowardice, injustice, he can never possibly be happy, even if the multitude, being utterly misled and deprived of their judgment, were to think him so, being corrupted by a double evil, pride and vain opinion, by which souls without ballast must infallibly be tossed about and driven out of their course; for these evils, above all others, injure the chief multitude of mankind.

(9) If, then, fixing the eyes of the mind steadily upon the truth, you should be inclined to contemplate the providence of God as far as the powers of human reason are capable of doing it, then, when you have attained to a closer conception of the true and only good, you will laugh at those things which belong to men which you for some time admired; for what is worse is always honoured in the absence of what is better, as it then usurps its place; but when that which is better appears, then that which is worse retires, and is contented with the second prize. (10) Therefore, admiring that godlike excellence and beauty, you will by all means perceive that none of the things previously mentioned were by themselves thought worthy of the better portion by God. On which account the mines of silver and gold are the most worthless portion of the earth, which is altogether and wholly unfit for the production of fruits and food; (11) for abundance of riches is not like food, a thing without which one cannot live. And the one great and manifest test of all these things is hunger, by which it is seen what is in truth really necessary and useful; for a person when oppressed by hunger would gladly give all the treasures in the whole world in exchange for a little food; (12) but when there is an abundance of necessary things poured out in a plentiful and unlimited supply, and flowing over all the cities of the land, then we, the citizens, indulging luxuriously in the good things provided by nature, are not contented to stop at them alone, but set up satiated insolence as the guide of our lives, and devoting ourselves to the acquisition of silver and gold, and of everything else by which we hope to acquire gain, proceed in everything like blind men, no longer exciting the eyes of our intellect by reason of our covetousness, so far as to see that riches are but the burden of the earth, and are the cause of continual and uninterrupted war instead of peace.

(13) Our garments are indeed, as some one of the poets says somewhere, "the flower of the sheep;" but with reference to the art displayed in their manufacture, they are the praise of the weavers. And if any one is proud of any glory which he may have acquired, being greatly delighted at his popularity among worthless people, he should know that he also is worthless, for he delights in them. (14) And let such a man pray to receive purification so as to have the disease of his ears healed, as it is through his ears that his soul is affected with great diseases. Again: let those men who are proud of their personal strength and activity learn not to be high-minded on such an account, looking at countless kinds of both domesticated and wild beasts, which are also endowed with great strength and power; for it is the most absurd thing imaginable for one who is a man to pride himself on the good qualities of beasts, and that too when the beasts themselves are thought of no importance whatever by him.

(15) Again: why should any man in his senses rejoice at beauty of person, which a short period must extinguish before it has flourished for any great length of time, since time always obscures its deceitful prime? and this too, when he sees that even in lifeless things there are objects of surpassing beauty, such as the works of painters, and sculptors, and other artists, displayed in paintings, and statues, and all kinds of embroidery, and weaving, which are held in the greatest honour in Greece and in the countries of the barbarians in every city. (16) Of these things, then, as I have said, not one is accounted by God worthy of the better portion.

And why should we wonder if they are not highly esteemed by God? for they are not even by those men who are very religious and devout, among whom those things which are really good and virtuous are held in honour, inasmuch as they have a good and well-disposed nature, and have improved their natural good qualities by study and practice, of which a genuine true philosophy is the maker. (17) But those who have devoted themselves to a bastard kind of philosophy have not even imitated physicians who give their attention to the body, the slave of the soul, though nevertheless they affirm that they are healing the mistress, that is to say, the soul itself; for then, when any such man is sick, even if he be the great king himself, passing over all the colonnades, and the men's chambers, and the women's chambers, and the pictures, and the silver and the gold, whether in money or in bullion, and the vast treasures of cups and works of embroidery, and all the rest of the celebrated ornaments of kings, and the multitude of his servants, and of his friends, or relatives, and subjects, and the chief officers who are about his person, and his body-guards, they come up to his bedside, paying no attention even to the decorations of his person, and not stopping to notice with admiration that his bed is inlaid with previous stones, or that his coverlet is of the finest workmanship and the most exquisite embroidery, nor that the fashion of his garments is of superlative beauty, but they even pull off the clothes in which he is wrapped, and lay hold of his hands, and press his veins, and feel his pulse, and note its beating accurately to see if it is in a healthy condition; very often too, they pull up his tunic and feel whether his stomach is too full, whether his chest is feverish, whether his heart beats irregularly. And then, when they have ascertained the symptoms, they apply the appropriate remedies.

(18) And in like manner, it would become philosophers who profess to be versed in the healing science as applicable to the soul, which is by nature the dominant part of the man, to despise all the things which erroneous opinion raises up as objects of pride, and to penetrate within, and to lay their hands upon the intellect itself, to see whether through passion its pulses are of an uneven rapidity and moving in an irregular and unnatural manner, and to touch the tongue, and see whether it is rough and devoted to evil-speaking, whether it is prostituted to evil purposes and unmanageable; also to touch the belly, and see whether it is swollen with the insatiable characteristics of desire, and, in short, of any other passions, and diseases, and infirmities, and to examine every one of those feelings, if they appear to be in a state of confusion, so that they may not be ignorant of what is proper to be applied to the soul with a reference to its cure.

(19) But now being lightened up all round by the brilliancy of external things, as being unable to see that light which is perceptible only by the intellect, they have passed their whole existence in a state of error, not being able to penetrate as far as royal thought, but being with difficulty able to reach the outer courts, and admiring those servants who stand at the gates of virtue, wealth, and glory, and health, and other kindred circumstances, they fall down in adoration before them. (20) But as it would be an extravagance of insanity to take blind men for judges of colour, or deaf men as judges of the sounds of music, so it is a most preposterous act to take wicked men as judges of real good. For these men are mutilated in the most important parts of themselves, namely, their intellect, over which folly has shed a deep darkness. (21) Do we then now wonder if Socrates, and such and such a virtuous man, has lived in purity? men who have never once studied any of the means of providing themselves with pecuniary resources, and who have never, even when it was in their power, condescended to accept great gifts which have been tendered to their acceptance by wealthy friends or mighty kings, because they looked upon the acquisition of virtue as the only good, the only beautiful thing, and have therefore laboured at that, and disregarded all other good things.

(22) And who is there who would not disregard spurious good things in comparison of genuine ones? But if while they received a mortal body, and were full of liability to all kinds of human disasters, and lived among such a number of unjust actions and unrighteous men, of which the very number is not easy to compute accurately, they were plotted against by their enemies, why do we blame nature when we ought rather to accuse the barbarity of those who thus set upon them? (23) For so in like manner, if they had been placed in a pestilential climate, they would inevitably have become sick; and wickedness is even more, or at all events not less, destructive than a pestilential state of the atmosphere. But as when there is rain the wise man, if he is in the open air, must inevitably get wet through, and if the cold north wind blows he must be oppressed by cold and shivering, and when summer is at its height he must feel the heat, for it is a law of nature that the bodies of men should be simultaneously affected by the changes of the seasons; so also in the same way a man who lives in such places,

"Where slaughters dire and famines might prevail,

And all the ills which thus mankind assail,"

must inevitably pay the penalty which such evils inflict upon him.

(24) Since in the case of Polycrates at least, in retaliation for the terrible acts of injustice and impiety which he committed, there fell upon him great misery in his subsequent life as a terrible requital for his previous good fortune. Add to this that he was chastised by a mighty sovereign, and was crucified by him, fulfilling the prediction of the oracle: "I knew," said he, "long before I took it into my head to go to consult the oracle, that I was anointed by the sun and washed by Jupiter," for these enigmatical assertions, expressed in symbolical language having been originally couched in unintelligible language, afterwards receive a most manifest confirmation by the events which followed them. (25) But it was not only at the end of his existence, but indeed during the whole period of his life from its earliest commencement that he was, though without being aware of it, making his soul to depend wholly on his body; for as he was always in a state of alarm and trepidation, he feared the multitude of enemies who might possibly attack him, being well assured that no one in the world was really well affected towards him, but that every one was hostile to him, and would turn out implacable enemies if he should be unfortunate.

(26) Again, if unsuccessful and yet of neverending precautions those writers who have written the history of Sicily are witnesses, for they say that the tyrant of Sicily suspected even his most affectionately loved wife; and a proof of this is that he ordered the entrance of his chamber by which she was about to have access to him to be strewed with planks, in order that she might never come upon him without being observed, but that the noise and tumult made by her stepping on these boards might indicate her approach beforehand; and besides this he compelled her to come not only without her robe, but even naked in every part, and even in those which ought not to be seen by men. And in addition to this he ordered the whole of the flooring along the road to be cut in width and depth like a trench made by farmers, out of fear lest anything should be secretly concealed so as to plot against him, which would inevitably be detected by the leaps and long steps which a person coming along this path would be compelled to take.

(27) Of how many miseries, then, was that man full who took all these precautions and practised all these contrivances against his own wife, whom he ought to have trusted above all other human beings? But he was like those men who scale precipices and climb over abrupt and steep mountains for the purpose of attaining to a more accurate comprehension of the natures of things in heaven, who at last after they have with great difficulty ascended to some overhanging ridge, find themselves unable to advance any further as they are too much exhausted to think of attempting the remaining portion of the mountain, and also want courage to descend, being giddy at the sight of the chasms and ravines below them; (28) for he, being in love with sovereign power as a godlike thing to be desired above all other objects, looked upon it as unsafe either to remain where he was or to retreat, for he considered that if he remained where he was innumerable other evils would come upon him in rapid and uninterrupted succession, while if he decided on retracing his steps his very life would be in danger, as there were enemies around, if not as to their bodies at all events in their minds, against him.

(29) And he also showed the truth of all this by the treatment to which he exposed a friend of his who spoke of the life of a tyrant as one of complete and absolute happiness; for, having invited him to a banquet which had been prepared in a most brilliant and costly manner, he ordered a sharp sword to be suspended over his head by a very fine thread, and when he, after he had sat down to the banquet, on a sudden perceived it, not daring to rise up and quit his place for fear of the tyrant, and not being able to enjoy any of the things which were prepared out of fear, he disregarded all the abundant and superb luxuries by which he was surrounded, and keeping his neck and his eyes turned upwards, sat in the expectation of instant Death.{2}{horace alludes to the story of Damocles, Od. III. 1.16 (which may be translated)--"Care murders sleep; the man who's learnt to dread / The sword unsafely trembling o'er his head, / In vain to court his sad distracted taste / The table groans beneath the varied feast. / Sad Philomel's untutored song is vain, / And vain the swelling flute's more laboured strain, / To close his eyes in sleep, the envied lot / Of weary peasant in his humbler cot."} (30) And when Dionysius perceived the state in which he as, he said to him, "Do you then at last begin to understand the true character of that illustrious and enviable life of ours, for this is what it really is if a man chooses to speak of it without flattery or disguise, since it contains indeed a great abundance of resources and supplies, but no enjoyment of any real blessing; and it causes its possessor incessant fears and irremediable and unavoidable dangers, and a disease worse than the most contagious or most fatal sickness, which is continually threatening inevitable death. (31) But the inconsiderate multitude, being deceived by the outward brilliancy and splendour of the position, are like people who are attracted by showy looking courtesans, who, concealing their real deformity under fine clothes and golden ornaments, and pencilling their eyes from want of any real beauty, manufacture a spurious beauty in order to lie in wait for and catch the beholders.

(32) Now men who are placed in situations of great prosperity are full of such unhappiness as this, of the greatness of which they themselves are fully aware, and they do not at all keep it to themselves, but like men who under compulsion divulge secret things, they often utter the truest possible expressions, which are extorted from them by suffering, living in the continual company of punishment both present and expected, just like cattle who are being fattened up for sacrifice, for they too are treated with the greatest possible attention in order to be fit to be sacrificed by reason of their fleshiness and good condition. (33) There are also some men who have suffered punishment, and that not concealed, but visible, and notorious for the impiety of the means by which they have acquired riches, the names and numbers of whom it would be superfluous to enumerate, but it will be sufficient to bring forward one instance as a specimen of the whole.

It is said, then, by those who have written the History of the Sacred War in Phocis that as there was a law established that any one who was guilty of sacrilege should be either thrown down a precipice, or drowned in the sea, or burnt alive, that those men who had pillaged the temple at Delphi, by name Philomelus, and Onomarchus, and Phayllus, divided these punishments among them, for that the first fell down a rugged and precipitous rock and was dashed to pieces on the stones, and that the second, when the horse which he was riding grew restive and plunged down towards the sea, was overwhelmed by the waves, and so fell alive into a devouring gulf; and Phayllus was wasted away by a consumptive disease (for the way in which the story is told about him is twofold), or else perished in the temple at Abae, being burnt in it when it was destroyed by fire. (34) For it must be the mere spirit of obstinacy and arguing to say that all these events took place by mere chance, for if indeed one or two of them had been punished at different periods or by some other mode of punishment, then it would have been reasonable to impute their fate to the uncertainty of fortune, but when they all died together and at one time, and by no other punishment but by that precise end which is appointed in the laws for the punishment of such crimes as those of which they had been guilty, it is surely fair to say that they perished by the direct condemnation of God.

(35) But if any of the violent men who are unmentioned, and who have at different times risen up against the people in their several states, and have enslaved not only other nations, but their own countries too, have still died without meeting with punishment, it is not to be wondered at, for in the first place man does not judge as God judges, because we investigate what is visible to ourselves, but he descends into the secret recesses of the soul without making any noise, and there contemplates the mind in the clear light, as if in the sun; for stripping off from it all the ornaments in which it is enveloped, and seeing its devices and intentions naked, he immediately distinguishes between the bad and the good.

(36) Let not us then, preferring our own judgment to that of God, assert that it is more unerring or more full of wisdom than his, for that is not consistent with holiness; for in the one there are many things which deceive it, such as the treacherous outward senses, the insidious character of the passions, the most terrible attacks of vice, but in the other there is nothing which can at all conduce to deceit or error, but justice and truth, by which each separate action is determined on, and in this way is naturally rectified in the most praiseworthy manner.

(37) Do not thou, then, my good friend, consider tyrannical power, that most unprofitable of all things, to be a seasonable possession; for neither is punishment disadvantageous, but it is either more beneficial, or at all events not injurious to the good to suffer due punishment, on which account it is expressly comprehended in all laws which are wisely enacted, and those who have established such laws are praised by every one; for what a tyrant is in a people, that is punishment in a law.

(38) When therefore a want and terrible scarcity of virtue seizes upon cities, and when a great abundance of folly overwhelms everything, then God, like the stream of an overflowing torrent, being desirous to wash away all the power and impetuosity of wickedness, in order to purify our race, gives vigour and power to those men who by their natures are fitted to exercise dominion, (39) for without a stern soul wickedness cannot be got rid of. And just as cities keep executioners for the punishment of murderers, and traitors, and sacrilegious persons, not because they approve of the dispositions of the men, but because they have need of the serviceable part of their ministrations; in the same manner the Ruler of this mighty city, the world, appoints tyrants, like ordinary executioners, to be over those cities in which he sees that violence, and injustice, and impiety prevail, and all other kinds of evils in abundance, that he may by these means put an end to their existence. (40) And then he thinks it right to pursue the guilty, as men who have been serving these vices from the impulses of an impure and pitiless soul, with every punishment imaginable, as the ringleaders; for as the power of fire when it has consumed the fuel which was given to it, at last consumes itself also, so also do those who have received supreme power over nations, when they have exhausted the cities and rendered them destitute of inhabitants, at last perish themselves among them, suffering due punishment for all that they have done.

(41) And why should we wonder if God employs the agency of tyrants to get rid of wickedness when widely diffused over cities, and countries, and nations? For he very often uses other ministers, and himself brings about the same end by his own resources, inflicting upon the nation famine, or pestilence, or earthquakes, or any other heaven-sent calamity, by which great and numerous multitudes perish every day, and by which a great portion of the habitable world is made desolate, on account of his care for the preservation of virtue.

(42) Therefore I have now, as I conceive, spoken at sufficient length on the present subject, namely, that no wicked man is happy, by which fact above all others it may be established that there is such a thing as providence; but if you are not thoroughly convinced, then tell me boldly what is the doubt which is still lurking in your mind, for then both of us by labouring together shall be able to see clearly what the real truth is. (43) And after some more arguments, he proceeds thus:--

God causes the violent storms of wind and rain which we see, not for the injury of those who traverse the sea, as you fancied, or of those who till the earth, but for the general benefit of the whole of the human race, for with his water he cleanses the earth, and with his breezes he purifies all the regions beneath the moon, and by the united influence of both he nourishes and promotes the growth and brings to perfection both animals and plants. (44) And if at times these things do injure those who put to sea or who till the land at unseasonable moments, it is not to be wondered at, for these men are but a small portion of the human race, and the care of God is exerted for the benefit of all mankind.

As, therefore, in a gymnastic school oil is placed there for the common benefit of every one, but still it often happens that the master of the school, by reason of some political necessity changes the arrangement of the usual hours of exercise, by which means some of those who wish to anoint themselves come too late; in like manner God, who takes care of the whole world as if it were a city committed to his charge, does sometimes cause the summer to resemble winter, and winter to assume the characteristics of spring, for the common benefit of the universe, even though some captains of ships, or some cultivators of the ground, may very likely be injured by this irregularity of the seasons. (45) Therefore He, being aware that the occasional interchanges of the elements with one another, out of which the world was made, and of which it consists, are a work of the greatest importance and necessity, supplies them without allowing anything to be an obstacle to them; and frost and snow-storms, and other things of that kind, follow the cooling of the air. And, again, lightnings and thunders arise from the collision and repercussion of the clouds, none of which things are perhaps effected by any immediate exertion of providence, but the rains and winds are the causes of existence, and nourishment, and growth to all things which are upon the earth, and these phenomena are the natural consequences of those others.

(46) For just as it often happens, when the master of a gymnastic school, out of rivalry, has gone to extravagant expense, then some of those who are ignorant of all that is becoming, having been bespattered with oil instead of water, let all the drops from them fall upon the boards, and then a most slippery mud is the result: nevertheless a man, whose appreciations were just would not say that the hard and the slippery state of the ground was caused by the intention of the master of the school, but that these things had resulted accidentally, in consequence of the abundant quantity of the things supplied. (47) Again, the rainbow, and the halo, and all other things of that kind, are natural consequences of those things becoming mingled with the clouds, not being occurrences which lead and influence nature, but being the results and consequences of the operations of nature.

Not but what these very things themselves do also afford some signs of great importance to wise men, for, guiding their conjectures by them, they predict calms and storms of wind, and fine weather, and tempests. (48) Do you not see that porticoes which embellish the cities? the greater part of these look towards the south, in order that those who walk under them may be warm in the winter, and may be cool in the summer.

There is also another thing which does not happen through the intention of Him who made it, and what is this? the shadows which fall from the feet indicate the hours to our experience. (49) And again, fire is a most important work of nature, but the consequence of fire is smoke, and nevertheless even this too at times is of some service. At all events in the heat, in the middle of the day, when the fire is rendered invisible by the brilliancy of the beams of the sun, the approach of enemies is indicated by the smoke, (50) and the principle which causes the rainbow is also the same which, in some degree, regulates eclipses.

For eclipses are a natural consequence of the rules which regulate the divine natures of the sun and moon; and they are indications either of the impending death of some king, or of the destruction of some city, as Pindar also has told us in enigmatical terms, alluding to such events as the consequences of the omens which I have now been Mentioning.{3}{this theory of the eclipses of the sun and other natural prodigies being prophetic of events on earth, is expressed by Virgil in a passage of the most exquisite beauty in reference to Caesar's death, Georg. 1.462 (as it is translated by Dryden)--"The unerring sun by certain signs declares / What the late eve or early morn prepares, / And when the south projects a stormy day, / And when the clearing north will puff the clouds away. / The sun reveals the secrets of the sky, / And who dares give the source of light the lie? / The change of empires often he declares, / Fierce tumults, hidden treasons, open wars. / He first the fate of Caesar did foretell, / And pitied Rome, when Rome in Caesar fell, / In iron clouds concealed the public light, / And impious mortals feared eternal night. / Nor was the fact foretold by him alone, / Nature herself stood forth and seconded the sun. / Earth, air, and seas with prodigies were signed, / And birds obscene and howling dogs divined; / What rocks did Aetna's bellowing mouth expire / From her torn entrails! and what floods of fire. / What clanks were heard in German skies afar / Of arms and armies rushing to the war. / Dire earthquakes rent the solid Alps below, / And from their summits shook the eternal snow. / Pale spectres in the close of night were seen, / And voices heard of more than mortal men. / In silent groves dumb sheep and oxen spoke, / And streams ran backward and their beds forsook; / The yawning earth disclosed the abyss of hell, / The weeping statues did the wars foretell, / And holy sweat from brazen idols fell. / Then rising in his might, the king of floods / Rushed through the forests, tore the lofty woods, / And rolling onwards, with a sweepy sway / Bore houses, lands, and labouring hinds away. / Blood sprang from wells, wolves howled in turns by night, / And boding victims did the priests affright. / Such peals of thunder never poured from high, / Nor forky lightnings flashed from such a sullen sky; / Red meteors ran across the ethereal space, / Stars disappeared and comets took their place. / For this the Emathian plains once more were strewed / With Roman bodies, and just heaven thought good / To fatten twice those fields with Roman blood."} (51) And the circle of the Milky Way partakes of the same natural essences with the other stars; but merely the fact that it is hard to account for, is no reason that those who are accustomed to investigate the principles of nature should shrink from examining into it; for the discovery of those things is most beneficial, and the investigation of them is intrinsically most delightful for its own sake, to those who are fond of learning.

(52) For as the sun and moon exist in consequence of Providence, so also do all things in heaven, even though we are unable to trace out accurately the respective natures and powers of each, and are, therefore, reduced to silence about them; (53) and earthquakes, and pestilences, and the fall of thunderbolts, and things of that kind, are said indeed to be sent by God, but, in reality, they are not so, for God is absolutely not the cause of any evil whatever of any kind, but the natural changes of the elements produce these effects, not as circumstances which guide nature, but as those which are followed by necessary results, and which do themselves follow naturally upon their antecedent causes. (54) And if some people, who think themselves entitled to immunity meet with some injury from these things, they are still not to find fault with their management and dispensation; for, in the first place, it does not follow, that if some persons are reckoned virtuous among men, they are so in real truth; since the criteria by which God judges are far more accurate than any of the tests by which the human mind is guided. And, in the second place, prophetic wisdom loves to contemplate those things in the world which are of the most comprehensive nature, as in the case of monarchies, and in the governments of armies, we see that it is not any obscure, ignoble, or chance person who is appointed to govern the cities or the armies.

(55) And some persons say that as on occasion of the slaying of tyrants, it is lawful that their relations also should be put to death, in order that transgressions may be checked by the terrible magnitude of the punishment inflicted: in like manner in pestilential diseases, it is necessary that some of those who are not guilty should be involved in the destruction, in order that others who are at a distance may learn moderation. Besides that, it is inevitable that those who are exposed to a pestilential atmosphere must become diseased just as all persons who are exposed to a storm on board a ship must be all exposed to equal danger. (56) But those wild beasts which are courageous have been created; for we must not suppress the truth (as if one were to anticipate the defence likely to be made by a man of powerful eloquence and tare it to pieces beforehand), in order that men may, by practising against them, acquire hardihood for the contests of war; for gymnastic exercises and continued hunting train men and inure their souls in a greater degree even than their bodies to rely upon their own courage, and energy, and strength, so as to disregard the sudden attacks of their enemies.

(57) But those men who are of peaceable character are at liberty to keep themselves not only within their walls, but also even within tents, and there to live in privacy, safe from the designs of any enemies, having vast and countless herds of domestic animals to help their enjoyment; since boars and lions, and animals of that kind, are by their own instinct driven to a distance from cities, not being inclined to expose themselves to danger in consequence of the devices of men. (58) And if any men, being influenced by a spirit of laziness and indolence, living without arms and without preparation, dwell fearlessly among the haunts of wild beasts, then if anything happens to them they must blame not nature but themselves, because when they might have guarded against any such disasters, they have neglected them. Accordingly, before now, I have seen at the horse-races some persons acting in a most careless manner, who, when they ought to have sat still and to have beheld the races in an orderly manner, standing in the middle have been knocked down by the horses' feet and by the wheels, and have met with a proper reward for their folly. (59) We have now, then, said enough on this subject.

But of reptiles, those which are venomous have not been called into existence by an immediate providence, but by the natural consequences of events, as I said before; for they are brought into life when the moisture which is in them changes to a more violent heat; and some are vivified by putrefaction, as, for instance, the putrefaction of meat produces maggots, and that which is caused by perspiration produces lice; but all those which are produced out of a kindred substance, and which have their generation in accordance with the usual spermatic principles which I have mentioned before, are very naturally ascribed to an immediate providence. (60) And I have also heard two accounts given of them as having been created for the advantage of mankind, which I should not think it well to conceal. Now one of them is the following.

Some persons have said that venomous animals contribute greatly to many of the objects of physicians, and that those who reduce that science to a regular system use them in a proper manner, and, acting with great wisdom and prudence, have discovered antidotes, so as to be able to contribute to the unexpected safety of those who were in the greatest possible danger; and even at the present time one may see those persons who apply themselves to the study of medicine, in a careful and diligent manner, using all these animals and plants in a most skilful manner in the composition of drugs.

(61) The other account has no reference to the practice of physicians, but only as it would seem to the studies of philosophers. For it says that all these things have been prepared by God as engines of punishment against offenders, just as generals and rulers prepare halters and chains. On which account, though they are quiet at other times, they are brought out with great power in the case of people who have been condemned, and whom nature in her incorruptible tribunal has sentenced to death; (62) for that they lurk in secret holes and in houses, is a falsehood; for it is seen that these creatures flee out of the cities into the fields and into desert places, to avoid man as their master. Not but what, if this is true, there is a certain sense and principle in it; for rubbish is heaped up in recesses: and quantities of sweepings, and refuse, and such things, are what venomous reptiles love to lurk in, besides the fact that their smell has an attractive power over them.

(63) Again, if swallows live among us, it is not at all strange, for we abstain from hunting them; and a desire of safety is implanted not only in the souls of rational creatures, but also in those of irrational animals.

But of those animals which tend to our enjoyment, there is not one which lives with us by reason of the designs which we form against them, except that some do live with those nations to whom the use of them is forbidden by the law. (64) There is a city of Syria, on the sea shore, Ascalon by name: when I was there, at the time when I was on my journey towards the temple of my native land for the purpose of offering up prayers and sacrifices therein, I saw a most incalculable number of pigeons on the roads and about every house; and when I inquired the cause of their being there in such numbers, they said that it was not lawful to catch them, for that the use of them had been prohibited to the inhabitants from the earliest ages; and so the bird had become so thoroughly tame through fearlessness, that it not only hovered about the roofs and came into the houses, but approached their tables also, and grew luxurious in the alliance which it had thus formed.

(65) And in Egypt we may see a still more marvellous thing; for the crocodile is the most odious of all animals, and one addicted to devour man; and it is born and brought up in the most sacred way, and although residing in the depths, it feels the benefits which it receives from mankind; for in those tribes, among which it is honoured, it multiplies in the greatest degree, but among those who injure it it never appears at all: so that there are places where even the most timid persons when sailing by leap out of their ships and swim about with their children.

(66) And in the country of the Cyclops, since the race of these men is a fabulous invention, there is no eatable fruit whatever produced except such as is raised from seed and cultivated by husbandmen, just as nothing is produced from that which does not exist; but we must not accuse Greece as being sterile and unproductive, for there is a great deal of deep and rich soil in it; and if the land of the barbarians is superior in fruitfulness, though it is superior in the food which it produces, it is inferior in the men who are nourished by the food, and for whose sake the food is produced.

For Greece is the only country which really produces man, that heavenly plant, that divine offshoot, producing that most accurately refined reason which is appropriated by and akin to knowledge; and the cause is this, it is the nature of the intellect to be rendered acute by the lightness of the air; (67) on which account Heraclitus said with great propriety, "Where the soil is dry, there the soul is most wise and most excellent;" and any one may conjecture this from the fact, that men who are sober and contented with a little are wise, and that those who are continually filling themselves with meat and drink are the least sensible, as if their reasoning faculties were drowned by the quantity which they swallow.

(68) And on this account we see, in the countries of the barbarians, trees and plants grow to the greatest possible size, by reason of the abundance of nourishment which they receive; and we see too, that the irrational animals which are found in these regions are the most prolific of any, but the mind is not so, or, at all events, it is so in a very slight degree, because it is elevated and raised out of the aether itself, while the incessant and uninterrupted evaporations of earth and water have freely boiled over it. (69) Again, the different kinds of fish, and birds, and terrestrial animals, are not grounds for accusing nature, which invites us to pleasure by those means, but are a terrible reproach to us for our intemperate use of them, for it was necessary, for the due completion of the universe, in order that there should be order and regularity in every portion of it, that there should be produced every possible species of animal. But it was not necessary that that animal, which of all others is most akin to wisdom, namely, man, should rush with such eagerness to the enjoyment of it, as to change his nature into something resembling the ferocity of wild beasts; (70) on which account, even up to the present time, those who have any regard for temperance entirely abstain from such things, eating only vegetables, and herbs, and the fruits of trees, as the most delicious and wholesome food.

And these men are instructors for those who look upon the practice of eating such animals to be in accordance with nature, and correct them, and are lawgivers to their respective cities, being men who take care to check the immoderate vehemence of the appetites, and who do not permit the unrestrained use of everything to everybody.

(71) Again, if roses, and crocuses, and all the other beautiful variety of flowers which we see, contribute to health, it would not follow that they all contribute to pleasure; for the indescribable variety of them makes the powers of some of them more conspicuous than those of others, just as there is a commingling of male and female, contributing to the generation of an animal; neither of them being calculated, by itself, to produce the effect which the two produce in combination.

(72) These things are said, in a most convincing manner, with reference to the rest of the questions raised by you, being quite sufficient to produce conviction in the minds of all who are not obstinately contentious on the subject of God taking great care of human Affairs.{4}{yonge's edition includes numerous miscellaneous fragments including From the Parallels of John of Damascus (which includes Greek fragments from Quaestiones in Genesis et Exodum, whose translation is generally based on Armenian), from An Anonymous Collection in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and from An Unpublished Manuscript in the Library of the French King. These have been relocated to an appendix in this volume.}

EVERY GOOD MAN IS FREE

Charles Duke Yonge's title, A Treatise To Prove That Every Man Who is Virtuous is Also Free.